Lets talk about Vim tabs today, because they seem to be a source of perpetual confusion for new users. Most conventional text editors use tabbed interfaces the same way as web browsers do. You take a file, and load it into a tab and that’s all there is to it. There is a direct, unbreakable, strict, one-to-one relationship between a tab and an edited file and it cannot be broken at run-time. You can’t for example load another file into an existing tab without either overwriting its contents. This is sort of the behavior we came to expect from tabbed interfaces.

Vim novices usually come with these preconceived notion of how the tab metaphor ought to work in a text editing context, and become confused when Vim refuses to play by these rules. To put it simply, tabs in Vim are different. They won’t work the way you expect them to, because they were not designed for that. The one file per tab convention is not the Vim way.

Let me preempt the obligatory self-professed “usability expert” snark comments about vim breaking established UI conventions: please kindly go fuck a hedgehog. Bill Joy was establishing his own conventions when he wrote vi while doing your mom long before she spawned you and then became so fat she developed her own event horizon. Complaining that Vim doesn’t implement tabs the same exact way Sublime Text does makes very little sense when you consider the huge architectural differences between these two editors.

The original vi editor, and earlier versions of Vim did not really support tabbed interface. They did however support editing multiple files with a single instance of the program using buffers. If you have ever progamatically manipulated text in some way, you should be familiar with the concept of a buffer. To put it plainly a buffer is the copy of your document that is held in memory as you manipulate it. When you open a file, you load it into a memory buffer, and that’s where your changes are applied as you work on it. When you start a new document, your text is held in a memory buffer until you decide to write it to disk. Vim maintains a list of buffers that it has currently open, and you can view it by issuing the :buffers command (or alternatively the shorter :ls command alias).

You can typically only edit a single buffer at a time, so the current (or active) buffer is the one displayed on your screen, while all the other buffers are hidden away. When you open a new file, a new buffer is created and immediately displayed. The buffer that was being shown before it is not gone, but simply hidden away. Buffers are “like” tabs in modern editors, only they don’t have a graphical UI representation. They work the same though – you activate one of them, and it’s contents become visible while all the other ones are hidden away.

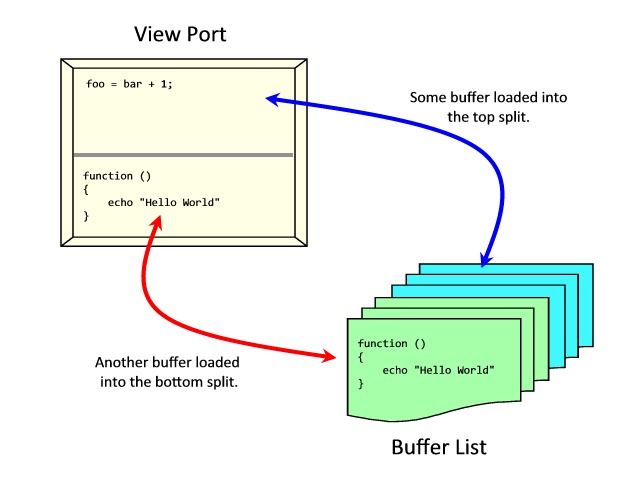

You can load any open buffer into your view-port by issuing the :b command followed by a number or partial file name which can be tab completed. The term “view-port” is a key concept here because it helps you understand what is really going on. It is best to think of the display area as a virtual port-hole through which you cane interact with your buffers one at a time.

When you create a split (for example using the :vsplit command) you effectively create two (or more) independent view-ports. Each one has access to Vim’s internal buffer list. So now you can have multiple buffers on the screen at the same time. Or you can load the same buffer in two splits, and watch changes you make on one side be automatically reflected on the other if that’s what floats your boat.

In essence, buffers do everything the tabs in say Sublime Text or whichever other Notepad replacement editor you happen to fancy. They just don’t have the clickable UI warts you might be tempted to fondle with your mouse. Lets face it – using a mouse to operate Vim is kinda like trying to eat tomato soup with a crossbow: it can probably be done, but it doesn’t seem at all practical. In fact, Vim’s buffer list is more flexible than most tabbed interfaces. For example, have you ever tried recursively loading your entire project tree into your editor? Let’s say you have 600 odd source files: what happens if you try to load all of them into your editor of choice? Firstly, chances are your app will crash and burn trying to prerender all these files or hitting some internal memory limits. It will also likely slow down to a crawl trying to create and display tabs in rapid succession (likely refreshing the screen for each one in the sequence). Assuming none of that will happen, your tab bar will likely become completely unusable: tabs will likely be about 1 pixel wide, or will force you to scroll around to find what you need.

Vim on the other hand will slurp up the entire project into buffers without even breaking a sweat because it doesn’t really have to render them unless you actually bring them into focus. Navigating a huge buffer list is actually easier than messing around with hundreds of tabs because you can use tab completion to match partial file names and get to where you need to go very quickly. Vim will also allow you to do bulk-edits using the :buffdo command which lets you run arbitrary vim commands (be it normal mode actions, build-in commands or function calls) on all the open buffers.

So the question is: could we simply force Vim to treat each buffer as a tab for the sake of following the UI convention followed by most of the relatively immature and untested (as compared to vim) editors on the market? The answer is no, we couldn’t. Why? Not because snobbery or entrenched traditionalism. It wouldn’t work because it would break the split screen functionality which is an established feature that predates the tabbed interface by a few decades.

Right now Vim lets you keep splitting your screen into independent view-ports, each of which can operate on a different buffer. How do you reconcile that with tabbed interface? Let’s say you have 7 files open, and you load 4 of them into 2×2 split (split horizontally, then split each half again vertically): what happens to the tabs that were loaded into splits of another tab? Do they disappear from the tab bar? What if you want to swap the contents of the splits? Do you re-shuffle the tab bar every time you split? If no, how do you deal with the tabs that are loaded in other tabs? If yes, how do you prevent tabs from moving around or getting lost? It seems like a very, very difficult problem to solve without altering existing functionality, with little to no benefit for existing users.

Tabs as implemented by Sublime Text and others simply make no sense in Vim world. Which brings us back to the original point of this post: what the fuck does Vim use the tabs for then? I can answer that with an example:

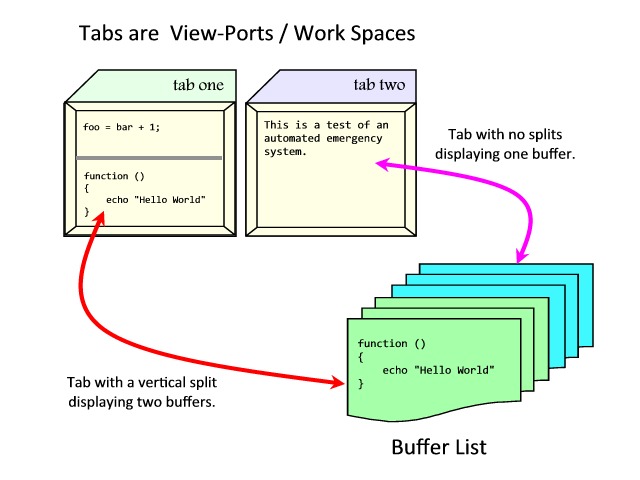

Imagine you are working on some code and you somehow ended up with a 2×2 split as above with 4 buffers on the screen at the same time. Suddenly you realize you need to open another file to tweak a thing or two related to your current task. You don’t want to split your screens any further, but at the same time you don’t want to blow that layout away since you are not done with it. To make matters worse said file is big, complex and ugly, so it ought to be viewed in full screen. In the olden days you would probably suspend (or minimize) your current session, and open another Vim instance to do so. But with tabs you don’t have to. You just open a new tab, which gives you a fresh view-port. One with access to the same buffer list, the same registers and recorded macros. One which you can split into multiple panes if you wish.

Vim tabs are essentially work-spaces or view-ports. They are more or less the virtual desktops for your text editor. They are not meant to be bound to buffers, but instead provide you with additional work surface where you can “spread out” the buffers you have opened.

You can of course try to force Vim to follow the “one-buffer-per-tab” convention, but it will always be an uphill battle. I’ve seen people write elaborate VimL scripts to accomplish this. I have seen countless plugins that claim they offer this functionality. But most of them break into thousand pieces as soon as you try to do something fancy with splits, hidden buffers or the :buffdo and :argdo commands. And if you are never going to try anything fancy, complex or weird then what’s the point of using Vim anyway?

Interesting. As you described Vim buffers, Emacs buffers work exactly the same way. We also occasionally have newbies showing up asking how to get tabs in Emacs, and all this information needs to be communicated in order to dissuade them. Another important feature (to me) of buffers is that buffers need not be associated with a file at all — just for use as scratch space. Any given Emacs instance of mine has on average a dozen such buffers open at any time.

You mentioned opening an entire project tree at once. Thanks to the buffer paradigm, I do this all the time! :-)

@ Chris Wellons:

Yeah, both editors seem to come out of the same sort of conceptual framework, though they diverged based on individual design choices. Vim was designed with the modal editing in mind aiming to minimize cursor movement over slow network connections, whereas Emacs was designed for aliens with 16 fingers on each hand ;) (I kid, I kid).

Oh, and you can totally open blank buffers in Vim. The :new command creates a split with a blank buffer and the :enew opens a blank buffer in the current window. There is also :tabnew which does that for tabs. Granted, vim will assume you meant to save these at some point and will complain if you try to quit without doing so.

I think the scratch.vim plugin implements the Emacs style scratch buffers.